Travel with Annita

Avid explorer and radio host Annita from Travel with Annita shares little-known facts, places to go, local cuisine and things to do for Black History Month. In this episode, she takes us on a journey to the Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historic Preservation Site.

By Michael J. Solender

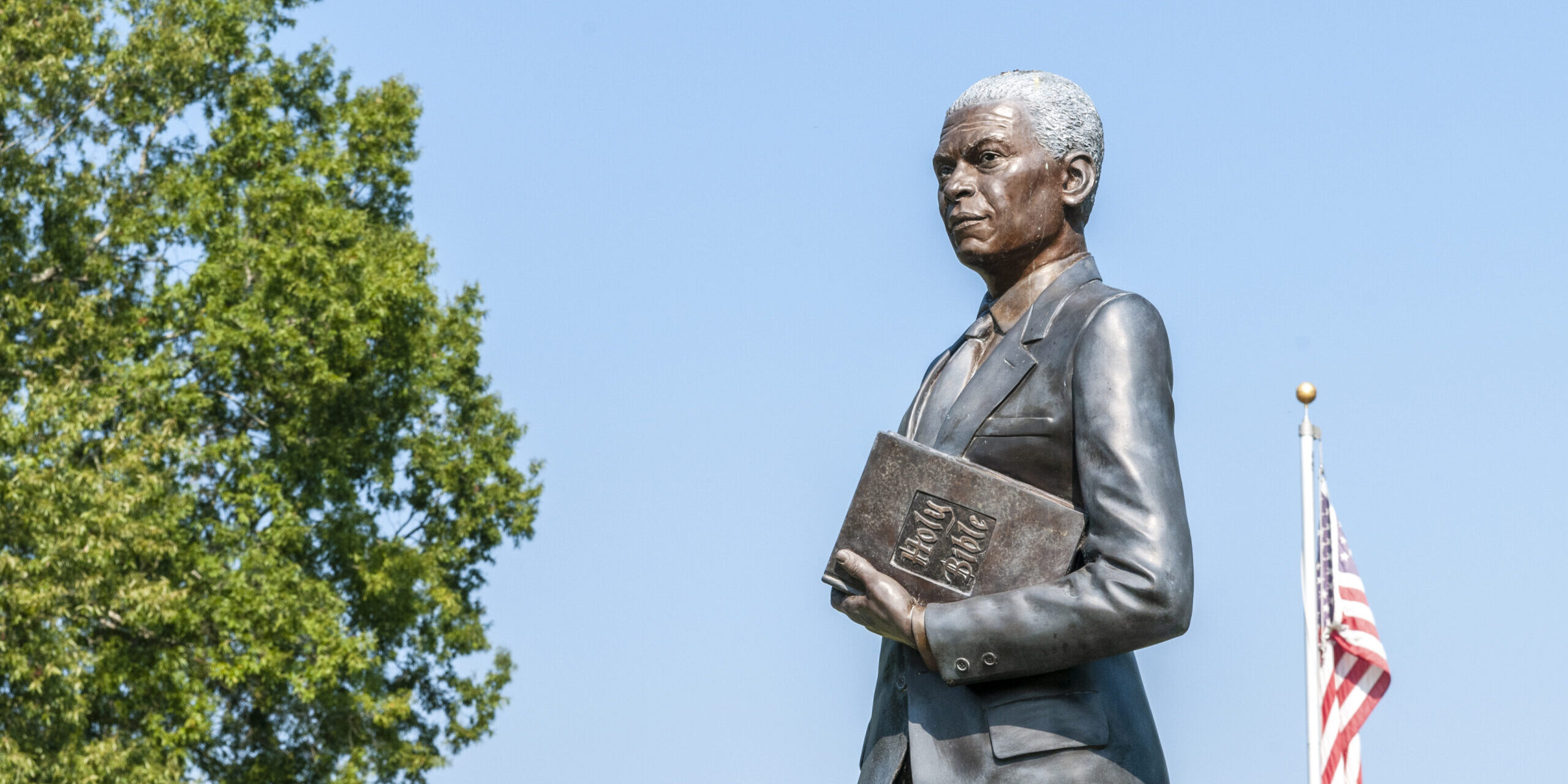

Greenwood, S.C.’s Benjamin E. Mays’ influence and impact on American history between Reconstruction and the modern Civil Rights era are unparalleled.

Visitors traversing the U.S. Civil Rights Trail through South Carolina’s Upstate are well served in ensuring Greenwood is high upon their list of must-see destinations. This modest community lays claim to the birthplace of Benjamin E. Mays, Greenwood County’s most distinguished native son. Here the Benjamin E. Mays Historic Preservation Site – a museum, cultural site, archives, and educational center – shines to share the story of a man from humble origins, born one generation removed from slavery, who went on to become one of the greatest educators of our time and mentor to our nation’s most notable Civil Rights leaders.

At its core, Mays’ story is a tale of overcoming great hardships, strife, and misplaced expectations of others. His belief in the values of hard work, determination, and education shaped the actions he took throughout his life as a servant-leader where uniting others in building community set him apart and led him to become an advisor to presidents and an international ambassador of human rights.

Education – A passport to accomplishment

Born in 1894 to former slaves and share cropping cotton farmers in the heart of Jim Crow South, Benjamin Elijah Mays learned early in life education would serve as a passport to accomplishment. Though he graduated high school at 22 as class valedictorian, his schooling accelerated, initially attending the all Black Virginia Union University, Bates College, and ultimately The University of Chicago where he earned his M.A in 1925 and his PhD. In 1935.

Born in 1894 to former slaves and share cropping cotton farmers in the heart of Jim Crow South, Benjamin Elijah Mays learned early in life education would serve as a passport to accomplishment. Though he graduated high school at 22 as class valedictorian, his schooling accelerated, initially attending the all Black Virginia Union University, Bates College, and ultimately The University of Chicago where he earned his M.A in 1925 and his PhD. In 1935.

Mays was Howard University’s first Dean of the School of Religion. Recruited to become president of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Ga., he navigated the College through near insolvency to become one of the nation’s most highly regarded Historically Black institutions of higher learning. He led Morehouse for 27 years and it was here Mays’ influence and reach grew exponentially and where he met, taught, and mentored a young Martin Luther King Jr.

Mays would become known as King’s “intellectual father” and inspiration for the Civil Rights movement serving as mentor and advisor to activists and pioneers Julian Bond, Maynard Jackson, Andrew Young, and others.

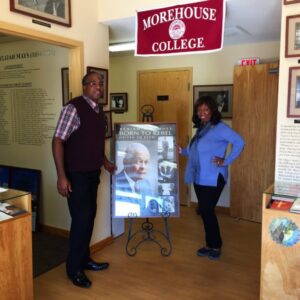

“He has had a long tradition of both activity and laying the intellectual foundations for what would become the civil rights movement,” says Christopher Thomas, historian, and director of the GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site. “When the movement kicks into high gear, Mays is 70 and he’d passed the flower of his youth to this army of young leaders he’d raised up.”

An extended chat with Thomas is the highlight of any visit to the Benjamin E. Mays Historic Preservation Site as his scholarly research of Mays’ lifework is exceeded only by his passion in sharing the Mays legacy. Reflecting on Mays, he noted his strong beliefs and character were developed early in Mays’ childhood.

“Mays was very bothered as a young person by this whole idea of Black inferiority,” says Thomas. “At 8 he said to his mother, ‘Momma, if God had made me inferior, I would never pray to a god like that.’ Mays would later clarify that he rejected the notion, a strong Southern doctrine at that time, that Black people were inferior to whites. Inferior in things like courage and mental capacity, inferior in things like culture and cultural identity.”

“Mays was very bothered as a young person by this whole idea of Black inferiority,” says Thomas. “At 8 he said to his mother, ‘Momma, if God had made me inferior, I would never pray to a god like that.’ Mays would later clarify that he rejected the notion, a strong Southern doctrine at that time, that Black people were inferior to whites. Inferior in things like courage and mental capacity, inferior in things like culture and cultural identity.”

One of Thomas’s favorite anecdotes about Mays, a story that illustrates his determination to bridge social, economic, and cultural divides, involves a long-term friendship Mays enjoyed with Gone with the Wind author, Margaret Mitchell.

“As Mays was addressing the financial problems at Morehouse in the early 1940’s,” says Thomas, “He writes Margaret Mitchell asking her to consider a contribution. She responded because of the uncertainties of time, with World War II, she couldn’t contribute at that time, but encouraged him to continue to write to her.”

Thomas explains how unusual, and socially taboo, it was at the time for a Black man to correspond with a married white woman, a Southern Belle of noted stature, no less. He noted their correspondence continued in “secret” with letters between the two traveling by courier and not through the mail, at Mitchell’s request. Subsequently, Mitchell made significant donations to Morehouse and they continued their correspondence up until Mitchell’s death in 1949.

“Margaret Mitchell donated enough money during her lifetime to Morehouse College to send 40 African American men to either medical or dental school,” says Thomas. “Her estate later made a $1.5 million contribution to Morehouse in the mid-1970s and people had no idea why.”

It was years later after one of the recipients of an anonymous “Margaret Mitchell scholarship,” Dr. Otis Smith, discovered the source of his medical education funding that the mystery unraveled.

It was years later after one of the recipients of an anonymous “Margaret Mitchell scholarship,” Dr. Otis Smith, discovered the source of his medical education funding that the mystery unraveled.

Upon learning of Mitchell’s gift, he in turn, contributed to the preservation of an historic Atlanta home where Mitchell wrote Gone with the Wind. A reporter covering the effort to save the Mitchell home, uncovered her correspondence with Mays. “It’s a tremendous thing that Mays, who would be so baptized as a young man into the racial violence that existed here and in America,” says Thomas, “Spent a lifetime building bridges between the segregated white and Black worlds and builds this relationship with Margaret Mitchell. It’s indicative of Dr. Mays’ desire to reach across barriers and walk hand in hand into a new day and time in America.”

Mays continued his love for education after retiring from Morehouse at age 69. He brought his considerable intellectual and relationship building heft to the Atlanta Board of Education where he served for nine years and went on to become its first African American president.

When Mays was called to eulogize Martin Luther King Jr. upon his assassination in 1968, he spoke of King and famously noted, “No man is ahead of his time. Every man is within his star, each in his time.” His legacy of service and bridge building demonstrate he was a man not only for his time, but one who continues to inspire generations beyond.

GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site.

229 N Hospital St.

Greenwood, SC 29646

864-229-8833

Charlotte, North Carolina’s Michael J. Solender has been captivated by great storytelling since his youth. He now writes about arts, travel, and curious people. His writing has been featured at the New York Times, Southern Living, Carolina Mountain Life, the Charlotte Observer, the Raleigh News & Observer, SouthPark Magazine, and others. Learn more about Michael and follow him on Twitter @MJSolender.

Interested in learning more about Benjamin Mays and his long-lasting and wide-reaching impact on the Civil Rights movement? Read more here and visit the historical site in Greenwood, SC for a tour with Rev. Chris Thomas himself!