Article by Michael J. Solender

Reverend Christopher Thomas, director of the GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site in Greenwood, shares energy and enthusiasm in promoting Mays’ legacy.

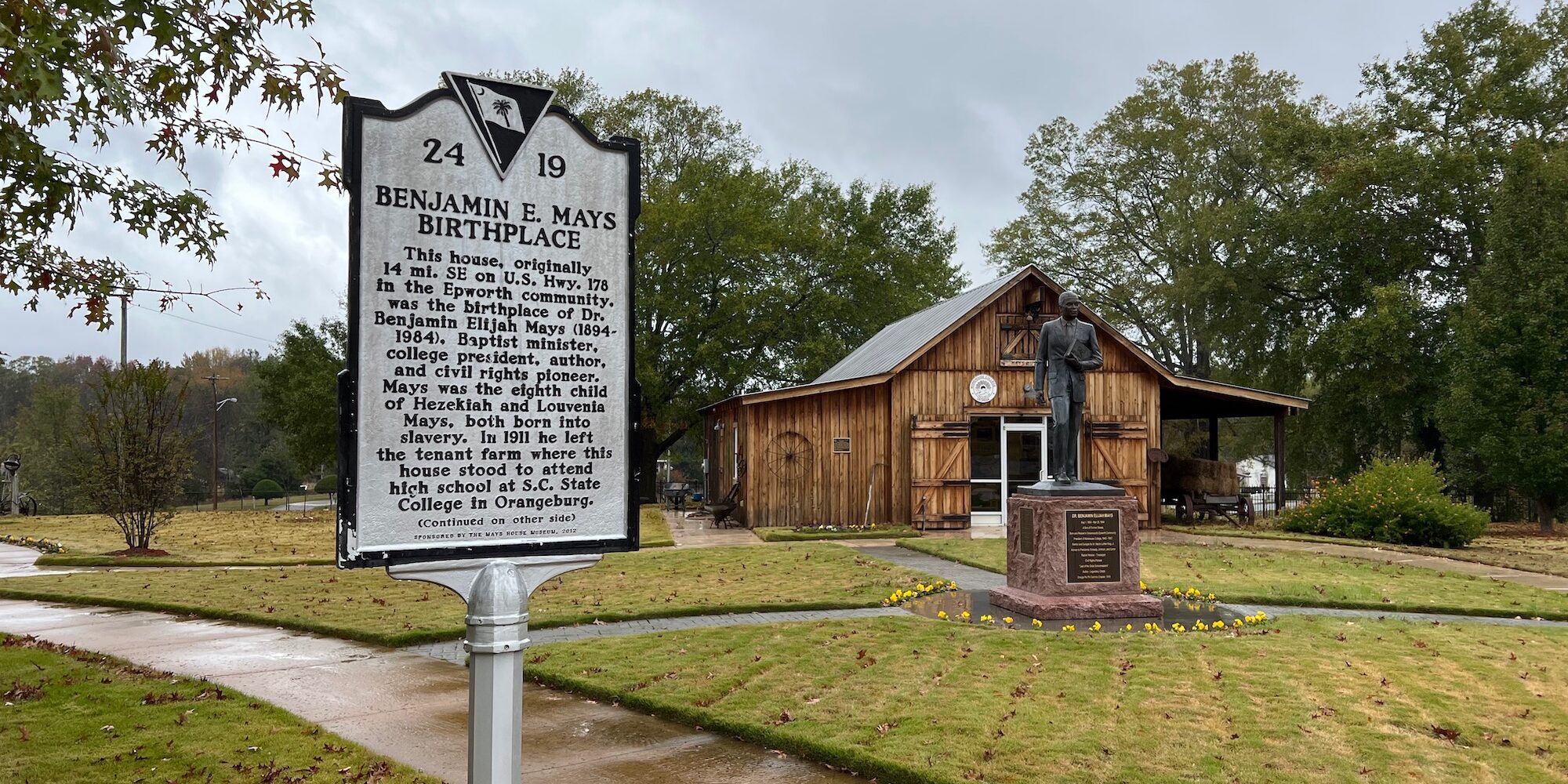

Few stops along the fabled U.S. Civil Rights Trail offer greater inspiration than the GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site in Greenwood, S.C. Birthplace of the Baptist minister, college president, author, and civil rights pioneer, the museum and cultural site offer visitors an immersive experience and unrivaled insight into the influence of the historic American leader of the 20th century.

Mays, widely known as mentor and intellectual father to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., provided inspiration for the contemporary Civil Rights movement and was advisor to activists and pioneers Julian Bond, Maynard Jackson, Andrew Young, and others. Through the course of his storied life, Mays met with and counseled presidents, world leaders and international figures as diverse as Mahatma Ghandi and Margaret Mitchell to JFK and Hank Aaron.

Despite his global sphere of influence and world-wide recognition, Mays remained true to the core values instilled in him from his earliest days on the small tenant farm in Greenwood – hard work, perseverance, and above all education would prove foundational to a life of service and accomplishment.

Reverend Christopher Thomas is director of the GLEAMNS Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Historical Preservation Site. He’s spent the past decade in service to the organization and through his dedication here has been instrumental in sharing the Mays legacy throughout the Old 96 District and Lakelands region of South Carolina and with thousands of annual visitors.

In 2021, South Carolina, through the Governor’s Awards in the Humanities program, recognized Thomas with the Fresh Voices in the Humanities Award. The honor distinguishes individuals who work in unique and innovative ways to use culture and history to bring people together.

Thomas works tirelessly to advance not only the teachings, lessons, and achievements of Dr. Mays, but to use those experiences as a platform for community discussion, collaboration, and understanding of democracy, equity, and social justice.

Visit Old 96 District recently spoke with Thomas about Dr. Mays and the site.

Visit Old 96 District: You have a familial connection to Dr. Mays, please tell us about that.

Christopher Thomas: Yes, my family comes from the same Epworth community that Dr. Mays was from. My great-grandfather knew him. He distinctly remembered when Dr. Mays left the farm to go to high school. And when my grandfather and my great aunts were going to South Carolina State, Dr. Mays, for 35 years, preached the Easter sermon there.

And in those days, that Easter sermon was their last day before spring break. Many of the families went to the church chapel service on campus. My great-grandfather did and was always smitten by the fact that he was just this little country farmer here. And when he’d walk into church, Dr. Mays would recognize him and bring him up to a seat in the front. And it was just a big deal for my great-grandfather to be thought of and honored in that way by Dr. Mays.

VO96: Given the significance of Dr. Mays’ lifetime of contributions to the American Civil Rights Movement, why does his legacy fly a bit under the radar?

CT: While the kind of work that Mays was doing was tremendously important and laid the foundation for King to be able to do what he did, I think he did it at a time where there wasn’t as much [recognition and] glory associated with it. When Mays was doing this work in the 30s, 40s, and 50s, it was laborious.

The Civil Rights Movement then was not branded in that way. Mays is called the principal founder of the Civil Rights Movement because it was his intellect, pen and leadership in organizations like the NAACP, the Urban League, the United Negro College Fund, and the [national] committees he sat on, and the recognition he received from [the likes of] President [Harry S.] Truman and JFK.

I try to get people to understand when they come here is that Mays was not born in a vacuum or in a bubble, King was not created in a bubble, there are areas of influence and history that affected Dr. Mays’ development, that established the creation of Morehouse College, that created historically black college and universities. The people like Mordecai Johnson who Mays meets in his first teaching stint that ultimately brings him to Howard to become the first Dean of the School of Religion at Howard University.

VO96: What’s the best way for people to experience their visit here, what can they expect to find?

CT: We are best known for being a tour destination, so the people that come here get a guided tour. I usually advise a visit of 90 minutes or so, depending on the group and questions they ask.

We tour the birth home. We talk about Mays’ early life here in Greenwood County. A lot of that is really experiencing not just life here in Greenwood County, but what life was like in rural America in the early 20th century. There’s consistency there no matter where you’re from, whether you were in Ohio or South Carolina or Kansas. Life for people back then was similar, they were mostly farmers. We share what Mays’ life was like through living history. We grow a cotton field every year. We grow a garden every year that usually has corn, snap peas, okra, and tomatoes.

For Mays, the struggle for people in rural environments who wanted to get off farms was different from region to region and race to race. Mays’ struggle was largely a struggle about the racial restrictions in the Old South. But it was also struggle about, generationally, his father wanting one thing for him and him wanting something else for himself. They’ll experience that conversation during the visit to the schoolhouse.

And then, inside the museum, we have more than 150 photographs of Dr. Mays with presidents, senators, government leaders and dignitaries. Visitors find [artifacts and ephemera] such as programs from King’s Funeral and Mays’ funeral, his yearbook at Bates College, his PhD robe and the trunk he traveled around the world with, his 50th anniversary graduation clock from Bates College, his [NAACP] Spingarn Medal.

There are things people will be familiar with, like photos of Dr. King, President [Jimmy] Carter, President [John F.] Kennedy, and Hank Aaron, who he mentored. We share all these stories and background and provide the context for people to make connections.

VO96: Why is Dr. Mays’ legacy relevant today?

CT: I don’t know if there was a more significant figure in American life in the 20th century than Dr. Mays. I think that he, the American clergymen that he associated with, and the movement that they were part of, are significant in not only demanding America give African Americans their rights, but also significant in directing America back to its core democratic principles. Because if those principles were not available to black citizens, then are they available to anyone?

Mays was significant in that. He was a defender and promoter of American values both in this country and around the world through his work with the Council of World Churches and with the YMCA, where he traveled around the world in 1930s. And Mays was a man that was very, very proud to be an American.

For us to reflect on who Dr. Mays was, and for us locally here in in Greenwood, South Carolina to also know that he was a native of Greenwood, we can say the origins of the Civil Rights Movement were born in the backwoods of South Carolina.

Much of what we’re seeing in our current climate are things that Mays experienced in his own life. And they’re just going back full circle. I think that if Mays was living today, he probably would continue the work that he had done in the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s, and even in the 70s, because that’s just his nature.

VO96: What do you hope people take away from their visit here?

CT: I would like people to come here and experience not just Dr. Mays, but the names and the likeness of people, black and white, who contributed to that history that I think have made America a better place today. My hope is that people come here are prompted to engage and have conversations about these experiences when they leave.

Charlotte, North Carolina’s Michael J. Solender has been captivated by great storytelling since his youth. He now writes about arts, travel, and curious people. His writing has been featured at the New York Times, Southern Living, Carolina Mountain Life, the Charlotte Observer, the Raleigh News & Observer, SouthPark Magazine, and others. Learn more about Michael and follow him on Twitter @MJSolender.

Interested in learning more about Benjamin Mays and his long-lasting and wide-reaching impact on the Civil Rights movement? Read more here and visit the historical site in Greenwood, SC for a tour with Rev. Chris Thomas himself!